Extensive research consistently supports cognitive processing therapy (CPT), prolonged exposure (PE), and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for treating posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). However, these evidence-based psychotherapies (EBP) face criticism for being inflexible, with randomised controlled trials lacking ecological validity. Concerns have been raised about their applicability to ‘complex’ clients in real-world setting.

To address these concerns, EBPs are now implemented more broadly, sometimes deviating from the original format. La Bash, Galovski, and Stirman (2019) use the ‘Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications’ (FRAME) to guide treatment modifications, specifically focusing on CPT.

Before delving into these concepts, La Bash et al. (2019) distinguish between treatment modification, adaptation, and fidelity. Treatment modifications involve changes to the protocol or delivery to enhance fit, engagement, or effectiveness. Adaptations, a type of modification, aim to maintain the essential elements driving treatment effectiveness. Fidelity is the degree to which a treatment adheres to the developer’s prescription.

La Bash et al. (2019) elaborate on why to adapt, goals, stakeholders, when to adapt, forms of adaptation, and measurement and evaluation. They stress considering these factors to maintain effectiveness and fidelity.

1. Why Adapt?

Regarding the reasons for adaptation, La Bash et al. (2019) propose responses to cultural and contextual factors, including:

- Socio-political factors (e.g., societal/cultural norms, political climate, mandates, and funding and resource allocation)

- Organizational/setting factors (e.g., available resources, billing constraints, service structure, location/accessibility, leadership support and time restraints)

- Provider characteristics (e.g., clinical judgment, cultural competency, previous training and skills, and perceptions of the intervention),

- Client characteristics (e.g., cultural factors, access to resources, comorbidity/multimorbidity, cognitive capacity, literacy level, comorbidity, immigration status)

They offer examples, such as CPT adaptations for language barriers in the Democratic Republic of congo (Bass, et al. 2013).

2. Goals of Adaption

Goals of adaptation include addressing policy constraints, improving outcomes, increasing feasibility, client satisfaction, and reducing costs. They emphasize the importance of clear goals to guide the adaptation process. For instance, Galovski et al. (2012) adapted CPT to include crisis sessions, addressing emergent life events. Chard (2005) extended and adapted the CPT protocol for individuals who experienced childhood sexual abuse.

3. Who is Involved in the Decision to Adapt?

La Bash et al. (2019) stress the importance of thoughtful involvement of stakeholders in decision-making, as their input shapes adaptation goals, forms, and timing. Key stakeholders include treatment recipients, team leaders, community members, researchers, and administrators. Input from both treatment providers and clients is critical for successful implementation, particularly focusing on enhancing engagement, comprehension, and impact.

4. When to Adapt?

Adaptations can occur at any point in treatment with La Bash et al. (2019) recommending early planning through pre-implementation assessments. La Bash et al. (2019) suggest that thorough pre-treatment assessments allow clinicians to carefully consider the need for adaptations while preserving effective elements of the original intervention. They further suggest that consultation with experts can inform adaptations and refine interventions.

For example, in a study where CPT with implemented on a population of Bosnian refugees, a proficient, but non-native English-speaking Bosnian refugee wrote his impact statement in English. After consideration of the clinical and cultural issues at hand, the client was asked to write and read their impact statement in their native language, which facilitated stronger emotional responses initially and, over time, greater reduction in distress when repeating the narrative [Schulz, Huber, & Resick, 2006].

5. Forms of Adaption

La Bash et al. (2019) highlight the following forms of adaptions:

- Treatment content (e.g., tailoring, substituting content, changing the length of sessions, substituting treatment module, repeating treatment elements, addition or removal of treatment components)

- Delivery of the intervention (e.g., format, setting, population receiving the treatment, language used to deliver the treatment, personnel delivering the intervention, session frequency)

- Staff training strategies

- Intervention evaluation method

One of the most common forms of adaptation is tailoring or making relatively minor changes to aspects of the treatment without substantial changes to the core intervention elements. Adaptation to intervention content can also include the addition or removal of a treatment component, such as adding a module on child development relevant to survivors of childhood sexual abuse to facilitate understanding of the impact that their childhood trauma childhood trauma on their adult functioning (Chard, 2005).

Adaptations are also being explored to better address the needs of active-duty military personnel, including a condensed 3-week PE protocol (Peterson et al, 2018), a condensed 2-week CPT protocol (Bryan, 2018), and a version of CPT in which the health care professional delivers CPT in the client’s home (Peterson, Resick et al, 2018).

6. Measurement and Evaluation

Measurement and evaluation methods include continuous quality improvement, program evaluation, open trials, and randomized control trials. La Bash et al. (2019) emphasise that thoughtful, theory-informed adaptations, supported by research and program-level evaluation, are essential for successful implementation.

Through their framework La Bash et al. (2019) highlight that treatment adaptations are not something that should occur on a whim, or purely ‘intuitively’ but that for adaptions to be successfully implemented they must be informed by theory, research, and program-level evaluation.

References:

Bass, J.K., Annan, J., McIvor Murray, S., Kaysen, D., Griffiths, S., Cetinoglu, T., et al. (2013) Controlled trial of psychotherapy for Congolese survivors of sexual violence. New England Journal of Medicine, 368(23), 2182–2191.

Bryan, C.J., Leifker, F.R., Rozek, D.C., Bryan, A.O., Reynolds, M.L., Oakey, D.N., et al. (2018). Examining the effectiveness of an intensive, 2-week treatment program for military personnel and veterans with PTSD: results of a pilot, open-label, prospective cohort trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74, 2070-2081.

Chard, K.M. (2005). An evaluation of cognitive processing therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 965-971.

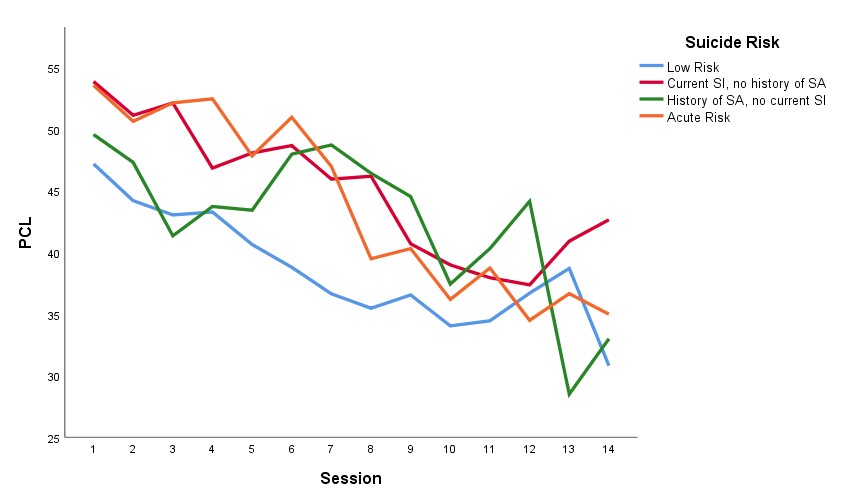

Galovski, T.E., Blain, L. M., Mott, J.M., Elwood, L., Houle, T. (2012). Manualized therapy for PTSD: flexing the structure of cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(6), 968–981.

Peterson, A.L., Foa, E.B., Blount, T.H., McLean, C.P., Shah, D.V., Young-McCaughan, S., et al. (2018). Intensive prolonged exposure therapy for combatrelated posttraumatic stress disorder: design and methodology of a randomized clinical trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 72,126–136.

Peterson, A.L., Resick, P.A., Mintz, J., Young-McCaughan, S., McGeary, D.D., McGeary, C.A., et al. (2018). Design of a clinical effectiveness trial of in-home cognitive processing therapy for combat-related PTSD. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 73, 27–35.

Schulz, P.M., Huber, L.C., Resick, P.A. (2006). Practical adaptations of cognitive processing therapy with Bosnian refugees: implications for adapting practice to a multicultural clientele. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 3(4), 310–321.